In the second part of the Nuclear Option series, the government led by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has abruptly committed to investing billions of pounds to establish operational modular nuclear reactors by the early 2030s.

The UK government is prepared to invest over £20 billion ($38 billion) from taxpayers’ funds to significantly boost the nation’s nuclear sector. This move comes as the challenging endeavor of decarbonizing the country’s energy sector becomes increasingly prominent.

Given the unlikely prospect of offshore wind and solar power providing continuous baseload electricity for Britain, the established objective is to achieve 24 gigawatts of nuclear energy capacity by 2050. This would constitute up to a quarter of the country’s power demand, a notable increase from the current 15 percent.

However, the development of large gigawatt-scale nuclear power stations is facing significant challenges in terms of progress. As a result, the government is placing growing emphasis on the timely implementation of small modular reactors (SMRs) to fulfill their expectations.

“The energy challenges experienced in Europe over the past couple of years have served as a substantial wake-up call. Prior to this, there was a blend of optimistic aspirations and deliberate overlooking of the complexities involved in our decarbonization efforts,” states Tom Greatrex, the CEO of the Nuclear Industry Association in the UK.

He mentions that while consecutive administrations at Downing Street have recognized the requirement for revitalizing Britain’s declining nuclear industry, the government under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is currently seized by a sense of immediacy. They have also acknowledged the pivotal role that taxpayers and public policy play in catalyzing this process.

“The universal lesson from regions across the globe where nuclear power has been adopted is that without active state involvement to foster its development, progress remains elusive,” remarks Greatrex. “Fundamentally, it’s public policy that has propelled its advancement, primarily due to the immense scale and capital-intensive nature of the infrastructure involved.”

The government has recently allocated a £170 million investment to accelerate the progress of the emerging yet substantial Sizewell C project, a 3.2-gigawatt nuclear reactor slated for construction by the mid-2030s. This funding supplement is in addition to the previous £700 million in subsidies.

However, the primary focus is compelled to shift to another location. The progress of the upcoming significant nuclear reactor, the 3.2-gigawatt Hinkley Point C facility in Somerset, has been plagued by seemingly interminable delays and significant cost overruns. Furthermore, out of the five antiquated large reactors currently in operation, all except one are scheduled for decommissioning within the next five years.

Therefore, the attention is firmly directed towards small modular reactors (SMRs), which hold the potential for more cost-effective and rapid deployment in theory. Additionally, there is a strong emphasis on advanced modular reactors (AMRs), which incorporate novel technologies or approaches that are predominantly in the conceptual stage or even mere possibilities within the minds of some scientists.

Seven days prior to the Sizewell revelation, the government officially declared its intention to establish a new agency, bearing the somewhat clichéd moniker of “Great British Nuclear,” aimed at invigorating the industry.

Up to £20 billion in subsidies could be allocated, if necessary, to facilitate the establishment of five to eight SMRs before the beginning of the next decade. Additionally, approximately £160 million in grants would be provided to sustain research and development efforts in AMRs and nuclear fuels.

“I eagerly anticipate the submission of world-class designs from various corners of the globe through the competitive selection procedure, while the UK positions itself prominently in the international competition to introduce an innovative era of nuclear technology,” declared Energy Minister Andrew Bowie with enthusiasm.

Leaders of the pack

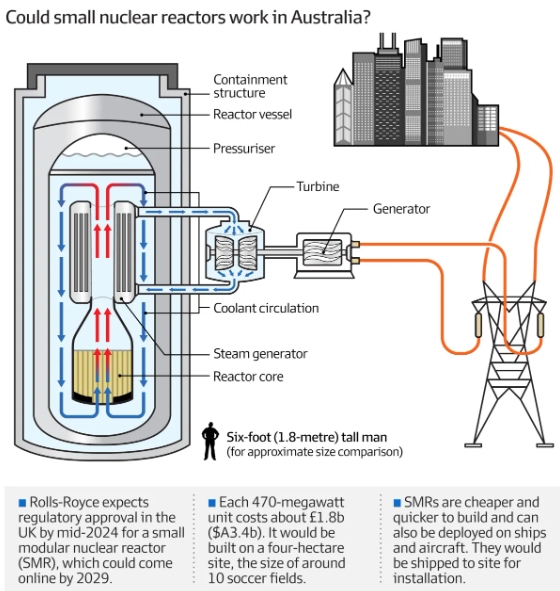

Leading the pack in the realm of SMRs is Rolls-Royce, at the helm of a consortium that has already secured £210 million in governmental grants. The company has significantly augmented its SMR team, now comprising around 600 professionals. Their reactor, derived from the pressurized water reactor (PWR) found in the UK’s nuclear submarines, is currently under assessment by the safety regulatory authority, the Office for Nuclear Regulation.

According to Alastair Evans, the Director of Corporate Affairs at Rolls-Royce SMR, their design is “at least 18 months ahead of any competing designs in the UK.”

“Rolls-Royce has been engaged in nuclear reactor plant design since the inception of the UK nuclear submarine program during the 1950s,” he explains. “The PWR design has been successfully employed in over 200 reactors globally… utilizing established and readily accessible technology to create a fully integrated, prefabricated nuclear power plant.”

Rolls-Royce’s primary competitor is GE Hitachi. According to media sources, GE Hitachi is currently in the process of constructing and undergoing regulatory assessment for its BWRX-300 model in Canada, while also being evaluated in the United States. The company asserts that it stands as the sole contender with a practical chance of achieving operational status for an SMR by 2030.

It’s highly probable that both Rolls-Royce and GE Hitachi will find their way onto the shortlist of Great British Nuclear, a selection that is expected to be finalized by the year’s end. Additional candidates in consideration might encompass Nuscale and Westinghouse. Those selected will gain entry to the government’s subsidy program, potentially amounting to £20 billion if necessary.

The precise nature of this generosity remains uncertain. It might adopt the “regulated asset base” framework, in which investors are ensured a guaranteed minimum profit, supported by a charge on consumer energy expenses.

An alternative approach could entail “strike prices,” which would establish a secured price per unit, aiming to mitigate the challenges and unpredictability linked with making substantial initial capital investments.

Regardless of the capital outlay, it will pale in comparison to the sum demanded by a large-scale reactor: approximately £2 billion to establish and activate an SMR, in contrast to the £20 billion or more designated for Sizewell C, owing to the SMR’s streamlined, factory-centric construction approach. The caveat, naturally, is that the output ranges from merely 50 to 500 megawatts of energy, as opposed to the 3.2 gigawatts delivered by larger counterparts.

“It’s the contrast between volume-based economics and scale-based economics,” remarks Greatrex.

The first set of SMRs will very likely be constructed at locations where larger reactors have been decommissioned: these communities are familiar with nuclear operations, possess strong grid connections, and the geographical conditions favor pressurized water reactors (PWRs). This approach could potentially address a range of potential challenges related to politics, planning, or permits.

Dark horses

While the SMRs are racing towards their goal for the early 2030s, the government aims to support different strategies over a more extended timeframe. The AMRs could potentially adopt technologies that demonstrate greater efficiency in the long run, like MoltexFlex’s molten-salt reactor. Alternatively, they might have diverse applications, as seen with local startup U-Battery.

U-Battery was in the process of designing a gas-cooled micro-modular reactor (MMR) that could be accommodated within a structure on land scarcely larger than a tennis court. Instead of contributing to the grid, this reactor had the potential to furnish independent heat and power to a singular enterprise or undertaking, be it a steel manufacturer, a hydrogen producer, a mining operation, a data center, or even a distant community.

Despite the support of its primary sponsor, Urenco, the endeavor struggled to attract investors, leading to the decision in March to transfer the intellectual property to the government-supported National Nuclear Laboratory.

Several other AMRs have garnered attention from prominent investors: TerraPower counts Bill Gates among its backers, while NewCleo has secured support from Italy’s Agnelli family. Many of these projects are engaged in diverse markets. For instance, X-Energy is utilizing funding from the US to establish a pilot of its gas-cooled pebble-bed reactor in Texas, a move it believes would facilitate rapid deployment in the UK.

“Having a couple of technologies in our arsenal would likely be advantageous,” remarked Paul Norman, the Director of the Birmingham Centre for Nuclear Education and Research, in a recent interview with The Times. “While you wouldn’t want an excessive number of distinct designs, a certain degree of diversity and competition among vendors is also desirable.”

The government has initiated the beginning, setting the stage for a race in Britain. With cross-party political backing and investor attention, Greatrex’s only concern revolves around the possibility of Westminster becoming sidetracked.

“It’s all about sustaining momentum and concentration. When a matter holds a prominent spot on the agenda, it naturally receives the necessary attention and dedication,” he explains. “However, if that attention wanes and the commitment dwindles, the progress and determination might also diminish. In such a scenario, the process could revert to being considerably time-consuming.”